A visit to “Gabrielle Chanel. Fashion Manifesto” at the V&A South Kensington

I have this rule called the “Birth of a Nation” rule. The rule states that if a historical actor did outsize harm for the time in which it existed, all discussion of that actor must call attention to the harm.

(Yes, I’m a wet blanket.)

Take, for instance, the film Jezebel from 1938. Jezebel promotes the racist, white supremacist, ahistorical notion that slaves were happy servants well-cared for and tended to by benevolent white masters. This is vile and it’s a blatant attempt to rewrite a bloody, brutal history whose legacy continues to harm black Americans today.

But, for the time, Jezebel wasn’t anything special in that regard.

The Birth of Nation is a different story. Released in 1915, The Birth of a Nation revitalized the Ku Klux Klan. The modern uniforms we associate with that particular terrorist organization come directly from The Birth of a Nation. It was the first film screened in the White House for the known eugenicist Woodrow Wilson, his cabinet, and his family. Even for 1915, this was outsized harm.

Not exactly a shining moment in the history of American cinema.

The problem is that The Birth of a Nation is seminal in the history of film for other reasons. The film was the first to have a musical score for an orchestra and the first to truly push fade-outs and closeups. It had a staged battle sequences that made a few hundred extras look like a few thousand. All of these were, unfortunately, groundbreaking. They were major advancements for film as a medium and for the field of multisensory storytelling.

But to discuss any of those advancements without also discussing the film’s repulsive white supremacist message is to implicitly co-sign that message, to suggest that the harm it did matters less than the ways it advanced the medium.

Clothing is communication. It is a medium by which we send and interpret messages, intentionally or otherwise. Therefore, it is subject to that “Birth of Nation” rule.

So, let’s talk about Coco Chanel.

It’s safe to say there was a spectrum in occupied France, even among the couture houses and associated fashion institutions. On one hand, you have Cartier’s remaining staff and designers gleefully antagonizing the Nazis and daring to flaunt their deviances. You also have people like Louise Carven, who sheltered her Jewish tailor, Henry Moise Bricianer, and also found safe hiding locations for his wife and underage children, all of whom survived the war thanks to her help.

Then, you have people like Lucien Lelong. President of the couture syndicate, Lelong took a pragmatic approach. If he wanted to keep couture in Paris and protect the industry’s artisans from deportation by keeping them employed, he needed to play professional ball with the Nazis — catering to the sartorial whims of their wives and mistresses, while keeping some personal distance. Lelong stood trial as a collaborator, but was found not guilty. His actions likely spared up to 12,000 non-Jewish artisans from deportation.

Slithering a bit closer to hell, we have Jacques Fath, Maggy Rouff, and Marcel Rochas, all of whom freely associated with the Nazis outside of business house and some of whom espoused anti-Semitic ideals.

(You can read more about this in Lou Taylor and Marie McLoughlin’s stellar Paris Fashion and World War Two: Global Diffusion and Nazi Control.)

And then, at the bottom of the pit, we get to Chanel. While Hal Vaughan’s Sleeping With the Enemy: Coco Chanel – Nazi Agent is still on my to-read list, the gist is that Chanel took up with an Abwehr agent, took part in a failed Nazi intelligence plot (Modelhut) and was, more generally, a wretched anti-Semite.

Chanel never faced consequences for her wartime actions, likely thanks to the influence of personal friend, Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

The Birth of a Nation was hugely influential in the development of not only filmmaking as an industrial practice, but film itself as an artform. Coco Chanel is one of, if not the most influential designers of women’s wear in the twentieth century. Neither should be venerated without serious discussion of the evil in which they actively partook.

“Gabrielle Chanel. Fashion Manifesto” is on now through February 25, 2024 at the Victoria and Albert Museum in South Kensington. It’s a beautifully conceived and executed exhibit, allowing viewers to trace Chanel’s evolution as a designer from her days as a milliner to her iconic suits, perfume, and purse.

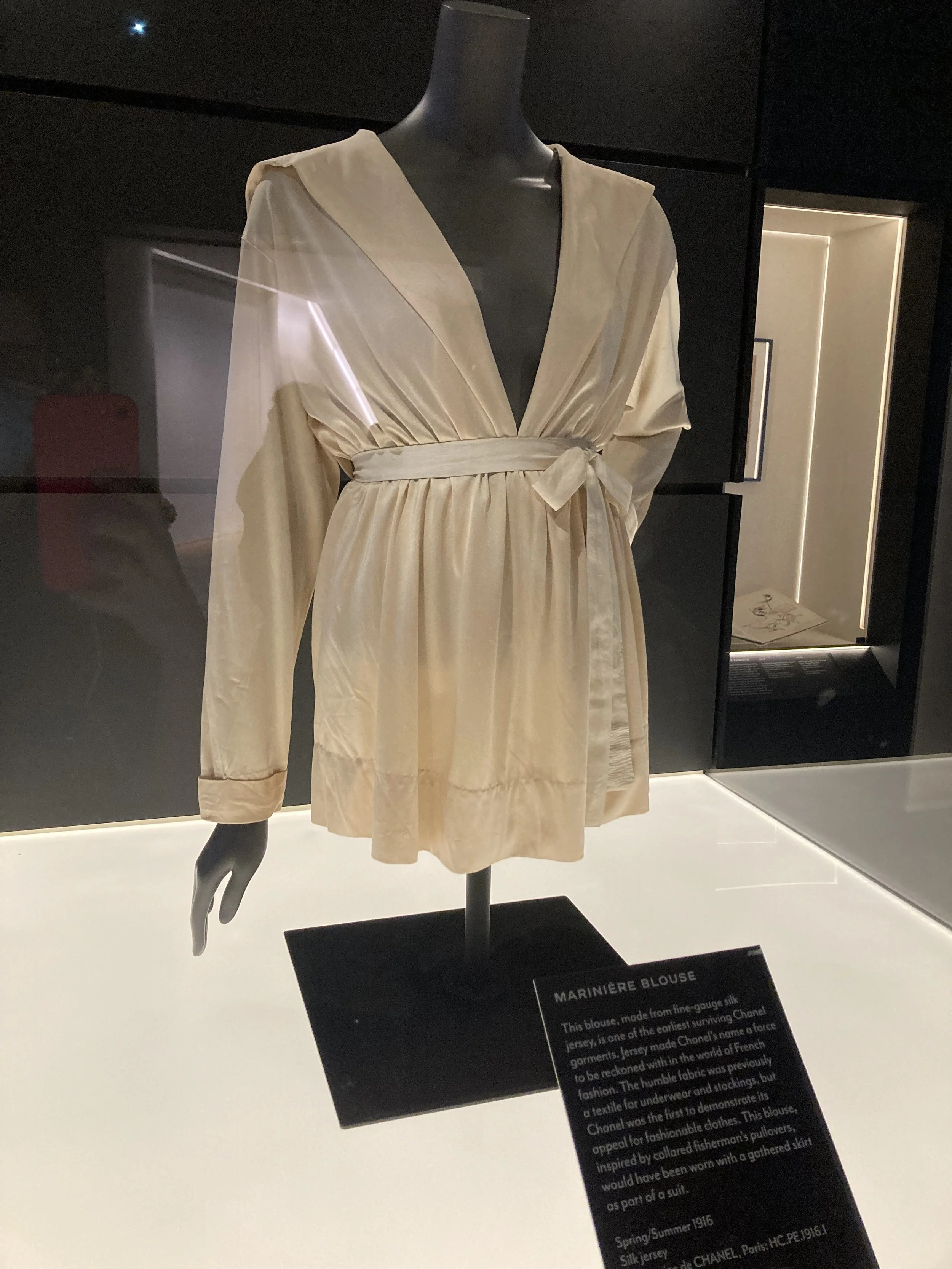

A Marinère Blouse. Please excuse any graininess, as the exhibit was designed to protect its artifacts, not facilitate photography!

Viewers begin with a spring/summer 1916 Marinère Blouse –one of the oldest surviving Chanel garments– and proceeds to her 1920s day and evening wear. Despite being nearly a century old, many of the garments on display still feel as if they might blend seamlessly into modernity, attesting to the long-lasting influence of Chanel’s design on western fashion.

The subtle seaming detail on the skirt front is one of my favorite things about this piece.

Some iconic 1920s silhouettes on display.

The exhibition also sheds light onto Chanel’s keen business sense by highlighting her expansion into textile design and manufacture, opening the door to a number of high-profile collaborations.

Chanel was a remarkably savvy businesswoman — and also a morally bankrupt one.

Viewers witness the birth of the little black dress and the sinuous lines that emerge in Chanel’s 1930s looks.

And then we get to the war.

“Gabrielle Chanel. Fashion Manifesto” opens with a large-scale timeline of Chanel’s life. On this period, it notes:

1940

Chanel renews a relationship with a German officer, Baron Hans Gunther von Dincklage. She appeals to his contacts to obtain the release of her nephew André Palaisse, a prisoner of war.

1943

Chanel is involved in an intelligence operation that sought to use her contacts to establish a direct line of communication between German officers and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

1944

Gabrielle Chanel is arrested at the Ritz by the French Forces of the Interior because of her relationship with von Dincklage. She is released after a few hours’ interrogation.

Let me be clear that I have my own crow to pluck with Christian Dior, but that’s a matter for another time.

As to the matter of the war itself, the exhibition notes:

In the war’s aftermath, thousands were arrested in France for associating with the Germans. Some were excuted. The Free French Forces detained and questioned Chanel, but she was released without charge. Chanel’s activity during the war continues to cast a shadow over her legacy and has been the subject of a number of articles and publications for the past 70 years.

Not mentioned: Chanel gave bottles of Chanel No. 5 away for free to American GIs.

None of this is technically wrong, but it’s some very careful phrasing. Chanel’s participation in Modelhut (which is detailed in another sign in the exhibit) was on behalf of the Nazis. She was, categorically, a Nazi agent — not just a mistress, but an active supporter, someone who actively sought to benefit from the Nazi’s genocidal purge.

Put bluntly: Chanel was a Nazi.

Now, there were plenty of Nazis who not only walked away free men and women, but even found renown after the war. In that regard, Chanel is hardly an exception. After all, Wernher von Braun was the lead designer of the Saturn V rocket, a consultant for Walt Disney, and the mind behind the V-2 rocket, which killed approximately 21,000 people and was manufactured by slave labor. Von Braun was open about his work and history — and yet, he was still posthumously awarded the President’s Award for Distinguished Civilian Service.

Chanel’s continued influence on fashion is so substantial that even a frank discussion of her wartime beliefs and politics would likely have little to no effect on her public standing; the iconic black dress, of course, predates the conflict and the suits came well after.

Such a blunt treatment, however, would implicate the audience, turning them from passive viewers to active judges. Can you venerate a work without venerating its creator? Does cultural impact absolve moral transgression? What are we willing to overlook in the name of beauty?

And what do our answers say about us?

This kind of confrontation, however, isn’t what most people want from an exhibit. It’s challenging, it’s uncomfortable, and it forces us to contend with our own values and what they might suggest.

It’s also worth noting here that the exhibit was created with the support of the Chanel brand, who have a vested interest in ensuring its founder’s affiliation with a genocidal regime not become front of mind. In that regard, while the verbiage isn’t as strong as I would have liked, it is still an attempt to hold the designer to a measure of account; though it’s hardly “saying the quiet part out loud,” it is nevertheless attempting to give the viewers some very pointed looks.

“Gabrielle Chanel. Fashion Manifesto” is a comprehensive, inoffensive look at a deeply questionable if legendary designer. Fans of the iconic suit will be delighted, while more casual observers will still appreciate the carefully designed progression and highlights. If you’re planning to visit, make sure to book your timed entry ticket well in advance or join the V&A for member access.