The Woman’s Institute of Domestic Arts and sciences was founded in 1915 as an offshoot of the International Correspondence School in Scranton, Pennsylvania. With courses in Dressmaking & Tailoring, Millinery, and Cookery, the school enrolled hundred of thousands of students from around the world. Once described by Governor William Cameron Sproul as “one of the big, outstanding educational institutions of Pennsylvania,” the Woman’s Institute has largely been forgotten, surviving in its remaining course materials and in the collections of a few dedicated institutions and collectors.

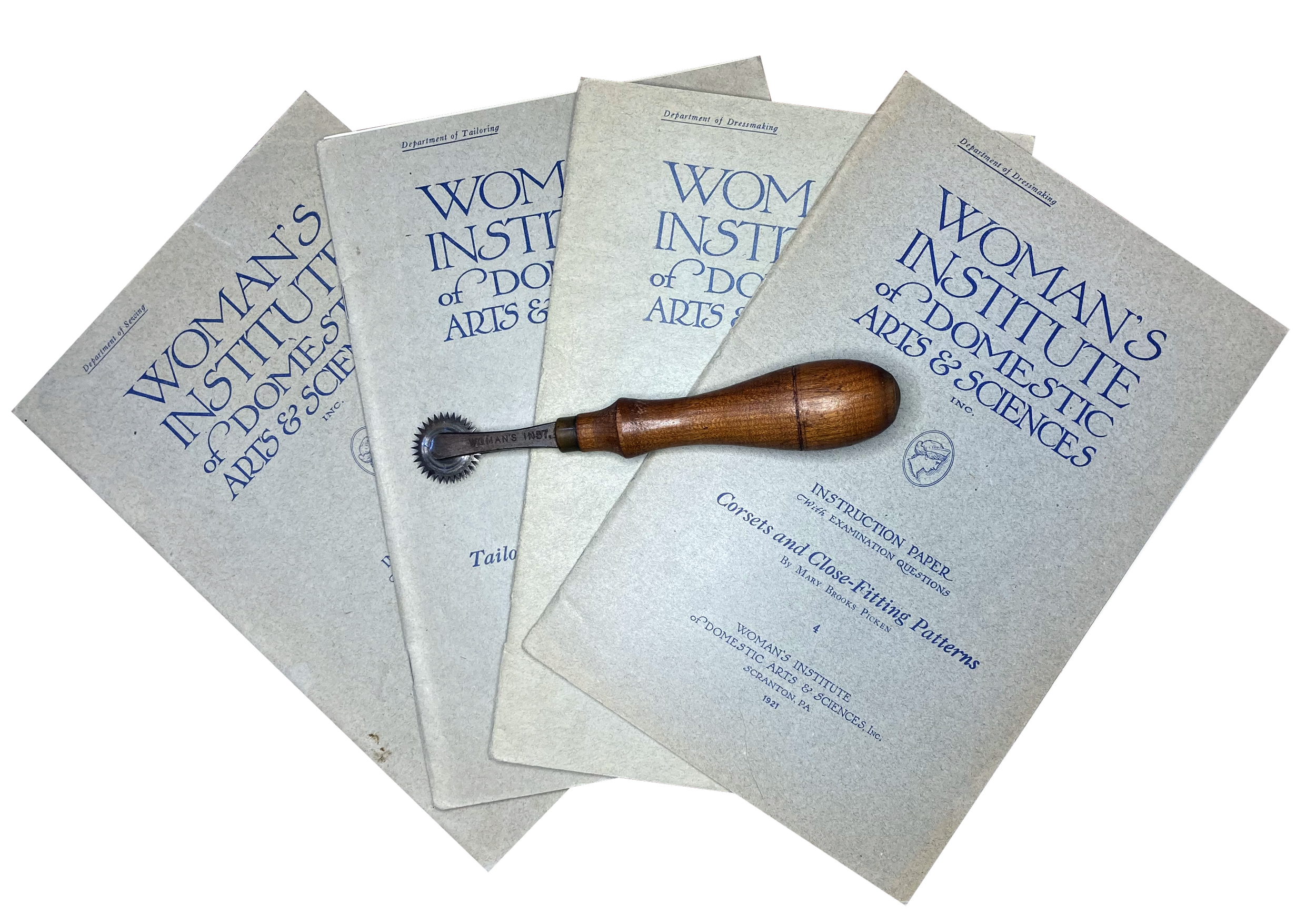

The Woman’s Institute was revolutionary, accepting students without regard to class, religion, race, or even gender, with even Marines stationed at Quantico enrolling in the Cookery program. Its greatest success, however, was the Dressmaking & Tailoring program, built on the shoulders of the Institute’s first Director of Instruction, Mary Brooks Picken. Among its students was Mary Hicks, daughter of Texas cattle ranchers, whose carefully preserved course materials survive to this day.

Now, more than a century after the Institute opened its doors, it’s time to shake off the dust and see how its teachings have stood the test of time.

Welcome to Mary, Mary, and Me.

Mary Brooks Picken

Mary Brooks Picken was a renowned sewing instructor and author. Born on August 6th, 1886 in Arcadia, Kansas, Brooks Picken would go on to become not only the first Director of Instruction for the Woman’s Institute, but one of five original directors of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute and the first woman trustee of the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York City. Along the way, she’d author ninety-six books, including most of the Institute’s core dressmaking and tailoring textbooks; serve as the fashion and dressmaking editor of Pictorial Review; and outlive not one, but two husbands.

Mary Brooks Picken understood that sewing could be more than chronically undervalued “women’s work,” that it could instead be a lifeline, a path to financial independence in a time when women were not even guaranteed the right to open a bank account. Brooks Picken was first widowed at twenty-four and supported herself offering instruction not only through the YWCA, but to the female inmates at the Leavenworth Penitentiary. One wonders just how much these experiences would go on to shape not only her educational philosophy, but her belief that women should be taught not just sewing skills, but business ones.

Mary Hicks

Mary Hicks was Mary Brooks Picken’s contemporary and, indirectly, her student. She was born on November 30, 1890 near Utopia, Texas and, in March 1918, began her tenure as a student of the Woman’s Institute. Mary would submit her first coursework on October 8, 1918 and her final assignment on April 26, 1924.

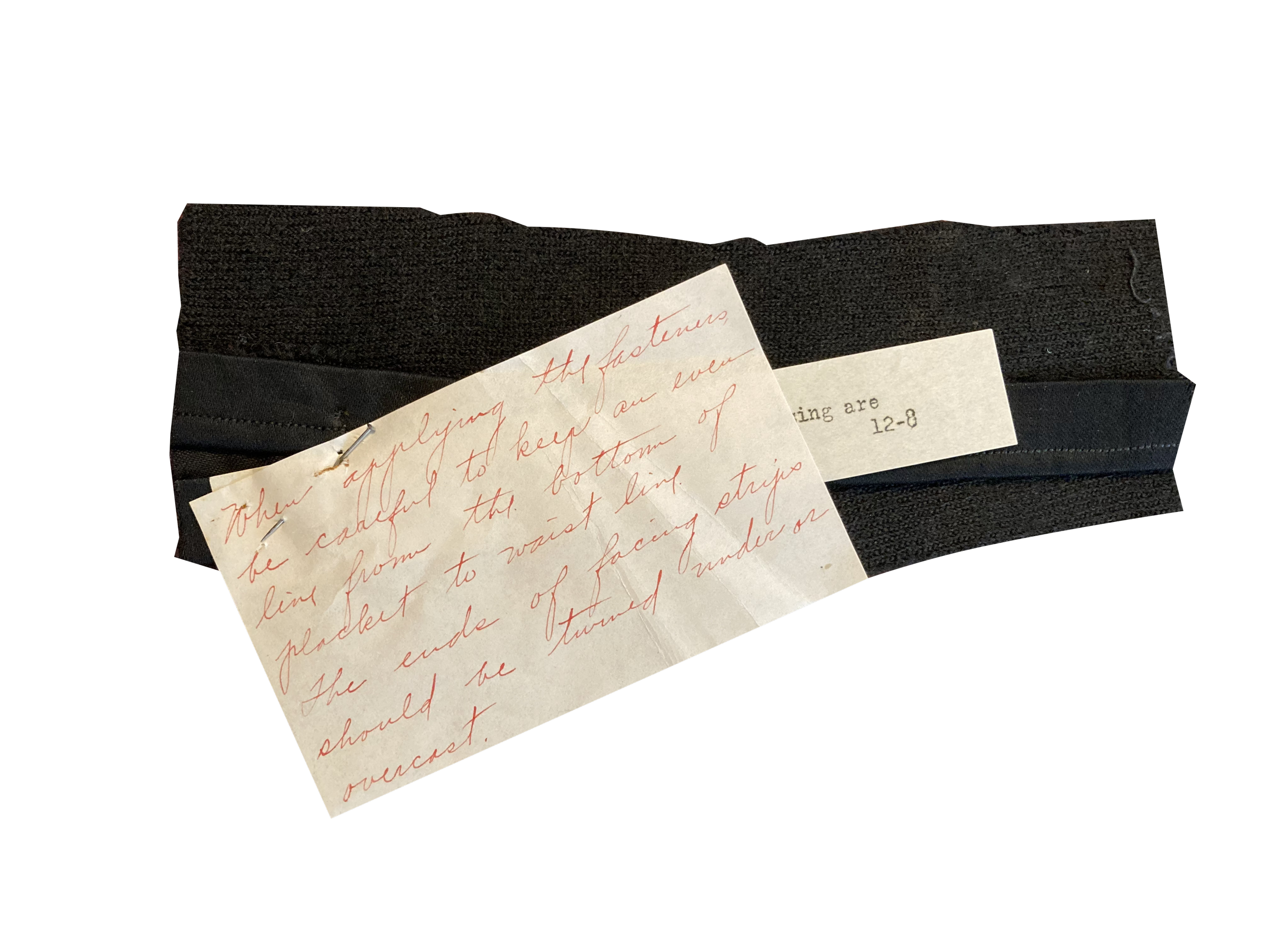

Mary was a diligent student and preserved much of her course material and correspondence. This collection was later discovered by her nephew and his wife whose dedicated efforts brought the work to the attention of Michaele Haynes of the Costume Society of America and, later, Dr. Catherine Leslie and Erin O’Brien of Kent State University.

The Institute’s student and faculty records are, by all accounts, lost to time and precious little material beyond the instructional books exists in public museum or archive collections. Mary Hicks’s work is, perhaps, one of the most complete surviving records and serves as a peek into the life of an Institute student. As such, it serves as the keystone to the entire project and I’m deeply grateful to Dr. Leslie for entrusting it to me.

Me

But who am I? I’m Sami. I’m trained as an instructional designer (read: I figure out how to teach things) and a journalist. By day, I’m a technical writer. By weekend, I run Good Water and Co. with my mom. And by night? By night, I sew.

I’m a New Yorker turned Pennsylvanian whose introduction to the Institute came in the form of trying to collect its marvelous, blue, hardcover books — compilations of the earlier lessons, published in the 1930s and early 1940s. Scrambling to collect them all would lead me down the rabbit hole of an oft-neglected piece of women’s educational history. As an instructional designer, a sewist, and an amateur historian, I’ve chosen to take on the full Dressmaking and Tailoring course experience, replicating it as closely as possible in an attempt to explore what made this school and these programs so special and so successful for so many years.

The Exceptions

Of course, I have had to make just a few adjustments.

Exception number one: Hand-sewing only. While the Dressmaking and Tailoring course materials assume students have access to a sewing machine, be it lock-stitch or chain-stitch, nowhere is this listed as a strict requirement. None of my antique machines are quite ready to go and using a modern machine feels like cheating. To that end, I have omitted machine-produced samples.

Exception number two: Quarter-scale. In the interest of full disclosure, fabric is expensive —especially high-end fabric—and I’m woefully short on places to wear late 1910s garb. As such, I’ve decided to create garments in quarter-scale as a matter of economy, practicality, and my hand-sewing speed.

Exception number three: Help. During the Institute’s operation, students could submit questions in writing and receive additional assistance. Given that the Institute has not served students since the early 1940s and that instruction via Ouija board is not a recognized pedagogical technique no matter how hard I try to summon Mary Brooks Picken, some allowances must be made in the event of confusion — chiefly, allowances for looking for modern day material online, but always with full disclosure.